'Brotherhood: Homage to Claudius Ptolemy'- a Poem by Octavio Paz

Hello Friends...

Sure, we all are doing well... Be careful, we must stay fit and shouldn't fall ill getting our studies affected. We shall eat and drink healthy, exercise regularly, and won't avoid our domestic and social responsibilities. And whatever time we get for ourselves at the end of the day, we must study hard for most of the time, so that we learn to think... and learn. We simply cannot afford to stop thinking, for we are learners, and we are the chosen ones who got the scope to learn...

Let's learn to think first...

The English Translation

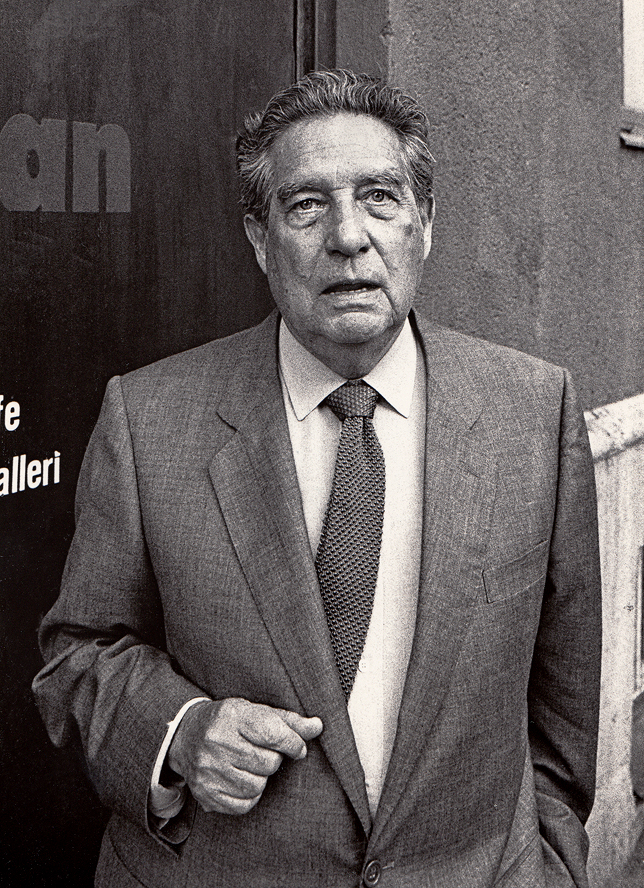

Today, we are going to study Brotherhood, a poem by Octavio Paz, the great Mexican poet. The text which we are going to study was translated from Spanish into English by Eliot Weinberger.

Let’s Listen to the Text First

As usual, I would like you to listen to the poem first, before you start reading the text on your own. Listening helps you to pick up the appropriate pronunciation, rhythm, and intonation; and thus, is likely to help you to get through the intended meaning of the text easily:

Did you find the recital helpful?. If you’re not sure, you needn’t worry right now. I’m sure you’ve got the sense groups identified at least. Let’s start studying the text on our own now, beginning with the title as usual:

Brotherhood: Homage to Claudius Ptolemy

I am a man: little do I last

and the night is enormous.

But I look up:

the stars write.

Unknowing I understand:

I too am written,

and at this very moment

someone spells me out.

The Title

Do you think the title might be helpful for understanding the text? Well, at least, it is supposed to be so, right? Do you feel that the text might be about some ‘brotherhood’ or ‘fraternity’?

Or is this a ‘homage’, or ‘tribute’ to Claudius Ptolemy? Who is Claudius Ptolemy, by the way?

Claudius Ptolemy

Let’s find the answer to the last question first, for it is more likely that we’ll get a definite answer here. Ptolemy [the ‘P’ remains silent] was an ancient scholar who is still remembered for his contributions to the field of mathematics, astronomy, and geography. Hit the link below if you feel to know a bit more about the great ancient scholar:

Now as you have already got introduced with Ptolemy and his works, it’s time to inquire if the poem is a tribute to him. Hence, we first need to figure out if there’s any particular reason for the poet to pay homage to this ancient scholar specifically. And certainly, we are not going to put the issue of brotherhood away anyway.

The Text

So, let’s start studying the text minutely once again, lines by lines, words by words, trying to trace clues to our probable answers.

A Personal Poem?

Here we have a first person narrator speaking through the text, isn’t it so? The text is very brief, consisting of just eight lines. And within this brief scope, we have the pronoun ‘I’ used for five times. Don’t you feel it noteworthy? It makes me feel that the text is very much a personal poem. The speaker is quite keen to share a very personal feeling with us, the readers. Just the problem lies in the fact that whatever the speaker wants to communicate with us seems to be like a puzzle encrypted, particularly from the fourth line onward. Do you agree? I think it’s time we should go beyond the text looking for the context.

The Context of the Text:

The Early Existentialists

Paz himself was greatly influenced by the existentialists. You need to realise that the effect of witnessing the devastation of two consecutive world wars within the short span of just half a century had left most of the sensible and sensitive contemporary people without any hope for humanity. They themselves suffered irreparable losses. They witnessed other people suffering losses. And they found to their utmost horror that all their virtues were not being enough to save them from the massacre. [And if you ask me, I would rather say that sensibly sensitive people do still bear the horror fresh in their minds.] After the second world war in particular, these people lost all their hopes upon the strength of humanity, its purpose, divine providence and poetic justice which earlier used to provide them the sustenance for their lives. Many among them lost their faith upon religion. What good is it if it fails to save its own virtuous followers? All of a sudden, they seemed to lose all the meanings of their lives. The whole world and their own existence turned out to be very much futile, or meaningless. This particular crisis was deeply perceived by great minds as Nietzsche and others who are considered to be the first generation of the existentialists. You may read the extract below from Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy to have a glimpse of the extreme pain and frustration of a sensible and sensitive mind rendered helpless living a futile meaningless life:

The best of all things is something entirely outside your grasp: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second best thing for you is to die soon.

Can you imagine how much pain and loss of faith is required to put an end to life? Can you imagine how much agony compels a mind to choose suicide as the only option left?

Later Developments

Later on, philosophers like Sartre and many others drifted away from such nihilistic pessimism [nullifying and rejecting human existence for its apparent futility] as they developed the school of existentialism further. Mankind used to accept that everything exists for a cause/purpose [essentialism] for long. There are many who still prefer to believe this way. However, Sartre and his followers contradicted this age-old belief of mankind and proposed that we ourselves assign meaning/purpose to our existence by making our own choices and deeds. It is not that we exist for a purpose, rather we exist [are born] without any purpose. However, we try to make our existence purposeful on our own. Octavio himself belonged to this second generation of the existentialists.

Do you feel to learn a bit more about this school of philosophy? You are welcome to hit the link below to listen to an easy discussion on the topic:

And if you are up for further details, I’m quite sure you’ll be able to look for materials on your own...

Back to the Text Again

Now, as we have already been introduced to the school of existentialists, let’s try to see if this has got any connection with this particular piece of puzzle. Let’s start reading the text once again from the beginning, shall we?

The First Line

The First Clause

Doesn’t the poem start with a strong, powerful, determined declaration?-

I am a man:

Does it sound too much masculine? Or do you think that ‘man’ here refers to ‘mankind’? I think it may be too early to conclude. Do you agree or not?

The Second Clause

Have you noted the colon after this very sentence/clause, in the middle of the very first line? There is a sentence/clause preceding the colon and another one following it in the very first line itself:

little do I last

Does this second clause sound to be as boastful as the preceding one? I’m afraid not. Rather, this inverted clause begins with the adverbial ‘little’ foregrounding/highlighting the despair of lasting ‘little’. Otherwise, commonly, one would have written 'I do last (for) little'.

Do you still prefer to think the ‘man’ here is particularly ‘male’, or would you like to consider the ‘man’ just a representative of mankind?

The Contradiction

Do you feel the first half of the line to be the reflection of the essentialists dominating our beliefs prior to the world wars, and the next half to be the reflection of the existentialists brooding and lamenting over the insignificant existence of mankind? If you agree, then you must note that here, the colon is not just being used to refer to the elaboration of the previous part, but also to strike a balance between the two contradictory philosophical thoughts. ‘I am a man’- if this part seems to be the boast of the most rational of the terrestrial life-forms [mankind], then ‘little do I last’ certainly implies the agony of those who have lost all hope for life and now stand shattered being insignificant and purposeless critically poised/placed against the limitless canvas of eternal time.

The Second Line

and the night is enormous.

Hence, to me, it seems justified to call this eternal time ‘night’ in the second line of the poem, for this time too is particularly cruel and unknown to us as is the night-time without any light to guide us through it in any direction. Do you agree? I would like to hear about it if you have a different opinion.

The Third Line

What do you feel about the third line?

But I look up:

Doesn’t the conjunction at the very beginning of the line ring a bell? Yes, ‘but’ is always used to mark a shift in an argument. So, even if the speaker laments after the existentialists in the first two lines of the poem, we may safely conclude that the speaker is far from being a nihilist [as many of the existentialists were/are] here.

Rather, s/he looks up soon aspiring for a scope to exert her/his existence, to find a purpose for her/himself. What do you think the colon is for here at the end of the line? To refer to what s/he sees, of course. In other words, the colon here refers to the elaboration that follows.

The Fourth Line

the stars write.

And s/he finds the stars to write. What may be the possible interpretation of this? Is the speaker referring to you,- her/his superstar readers writing down important notes carefully by the margin?

No?

What are these stars then?

Why don’t you check the sub-title of the text now once again? Remember, the text might be a tribute to Ptolemy, the great ancient astronomer? Then, shall we consider these to be the real cosmic stars surrounding us? But does this reading help us at all? How can cosmic stars write?

Could you recall how we have read ‘night’ metaphorically earlier? Is there any possibility that we can read this expression as a metaphor?

The Metaphor

Yes, of course we can. What is writing, essentially? It signifies presence, presence of a thought, the thought of/conveyed by the author. So, in a sense, writing reflects the presence of the thinker, or the author. Likewise, as we too look up into the sky with the speaker, we find the cosmic stars above to exert their presence, with their regular rhythmic motion in the universe.

The Fifth Line

Now shall we move on to the next line? How can we understand anything without knowing it? Any idea how are we to interpret the line?-

Unknowing I understand:

Exposure to knowledge or information through our sensory organs precedes our understanding of the knowledge or information. We may understand what we come to know, right? What we don’t know cannot be understood by us. I hope you’ll agree.

Intuituion, or Epiphany

But, there are certain moments, or incidents that we can predict, is it not so? Often we can predict the weather conditions based on our own previous experiences of the different factors influencing the weather. Such understandings are often achieved through our sixth sensory organ, or intuition, which is nothing but the cumulative functioning of all our previous experiences thoroughly assimilated. So, we may take the liberty to interpret this as an intuition, or an epiphanic revelation, the knowledge that is gained beyond the sensory perceptions.

And this time, I feel quite confident that you’ve already noticed the colon at the end of the line, and are ready for the explanation/elaboration of the understanding of the speaker.

The Sixth Line

I too am written,

The speaker also is written;--- s/he composes her/his text, and her/his text writes/exerts her/his meaningful existence here on earth. The speaker has finally been successful to assign some meaning/purpose to her/his existence following the existentialists like Sartre.

Don’t you feel the speaker here seems to share the same philosophical belief of the poet himself? Interesting, isn’t it?.

The Last Two Lines

Let’s read the last two lines of the poem. Here we have a single clause expressed through the last two lines of the poem. I’m pretty sure you still remember that the first line of the poem, in sharp contrast, consists of two clauses.

and at this very moment

someone spells me out.

Do you get the dramatic twist? Who is spelling whom out right at this moment? It is the reader [us] who are reading the poem/the text right now.

Don't we now understand that the speaker is actually the poet himself for he is being spelt out right now?

It’s indeed a personal poem. Throughout the poem, the poet-speaker has been trying to refer to the purpose he has chosen to assign to his existence to render meaning to it. And to prove his significance as a poet, he chooses to point out to the fact that right now we are discussing his writing/poem, thereby exerting his significance and worth as a poet.

Smart strategy, isn’t it?

As the stars define their own courses through their regular rhythm, our poet also exerts his own course of existence through the rhythm of his poetry. As soon a reader spells out his rhythm, he too gets written in the history of the universe.

In this connection, we may read [or you may skip for now, if you’re already exhausted] what Octavio says in his poem 'Poetry' (La Poesía, 1942):

Because I only exist because you exist,

And my mouth and my tongue were formed

Only to say your existence

And your secret syllables, word

Impalpable and despotic,

Substance of my soul.

Back to the Title Again

Ptolemy

Shall we get back to the title once again? We are yet to conclude about the title, have you forgotten? The extract from the epigram of Almagest, Book I by Ptolemy may provide us a lead to the thematic thrust of the poem:

Well do I know that I am mortal, a creature of one day. But if my mind follows the winding paths of the stars then my feet no longer rest on earth, but standing by Zeus himself I take my fill of ambrosia, the divine dish.

Bond of Fraternity

Ptolemy too had felt the pangs of the insignificance of brief human life, but he was aware of his significance as well, often reminded by the stars above. It seems that the winding path of the stars up there in the sky made the ancient scholar feel as important as Zeus himself. Long after Ptolemy, Octavio also looks up to the stars above for inspiration to write, to assign significance to his apparent purposeless life, and finally succeeds. Hence, he feels a connection, or bond of brotherhood existing between him and the ancient scholar, and chooses to pay homage to him. The title, thus alludes to the classical astronomer, and binds the entire time period from the classical age to this post modern era with the cord of fraternity.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment

Please feel free to share another perspective, suggest an upgrade, and ask for information, or about a doubt or confusion...